The Last of Us offers no shortage of challenges to players’ survival, and perhaps none are more imposing than the various Infected Joel, Ellie, and others encounter. They vary in size and tactics, all memorable in their own right, but one of the most iconic among them is the Clicker, one of the first Infected players come across in The Last of Us Part I.

Whether you encountered these foes when the original The Last of Us debuted in 2013, watched their live-action versions appear on The Last of Us on HBO, or have recently experienced them in The Last of Us Part I on the PlayStation 5 console, or are planning to play Part I on PC starting March 3 via the Steam or Epic Games Store, the Clickers are not to be taken lightly.

Following our deep dive into The Last of Us’ unforgettable opening for our series Building The Last of Us, we next spoke to members of the Naughty Dog team both from the original TLOU and in Part I to make these Clickers, well… click, and about how the TV show’s creators tackled bringing the tension of TLOU combat to live-action.

Creature Creation

The Last of Us’ Clickers are an immediate threat when introduced to players, but they of course had to feel natural to The Last of Us’ unique take on a post-pandemic world.

“When we started working on the [The Last of Us]…It was very clear you’re going to fight other factions, other humans as they’re trying to survive, and you will have competing goals. That was very clear. And then we’re like, ‘Do we even want the Infected?,’” Naughty Dog Co-President Neil Druckmann explained.

The team considered keeping The Last of Us so grounded as to only have human enemies, but in realizing another enemy type could help showcase the idea of what brought mankind to the brink, the germ of the Infected was born. But they didn’t suddenly spring to life fully formed.

“We were always wary of how we differentiate ourselves from zombies, because there have been a lot of zombie movies, a lot of zombie games, and we could easily fall into that trap of just being one more zombie thing without having some fresh take on it,” Druckmann said, explaining that a specific piece of art during the concepting phase solidified where the team could take the Infected.

“Hyoung Nam, one of our concept artists, eventually did this mash up…he took these fungal growths, these photographs of them and this person that was slumped against a wall and bashed them together, so this person that was against the wall, just covered in fungus, you couldn’t even see their face anymore,’” Druckmann said.

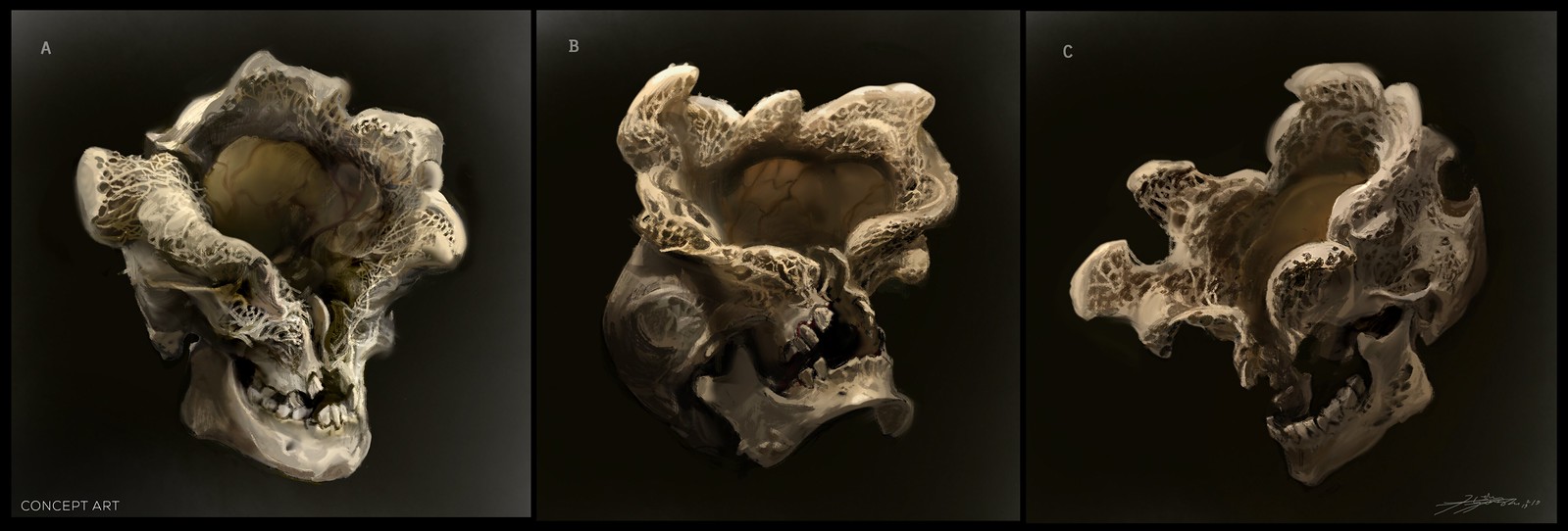

From there, the team kept iterating and refining this core idea of what the infected could be, including the idea that the Cordyceps infection at the heart of this outbreak would grow into a person’s brain and split open their head, leading to what eventually became the iconic look of a Clicker’s head.

“We tried to be true to the idea and the concept of the Cordyceps,” Art Director Erick Pangilinan said. “That unique bloom in the head is how we were trying to tie that back into the Cordyceps idea. The Clicker bloom was definitely an ‘Ah, ha!’ moment.”

Just as important to conveying the fear the Clicker strikes in players is its movements. The quick snaps of its neck, the flicking of its limbs – every step the Clicker takes is one scary step closer to it discovering you. But, as Lead Cinematic Animator Bryant Wilson, who worked on The Last of Us Part I and Part II, describes it, his personal philosophy when animating a Clicker’s movement is rooted in an idea that stays true to Nam’s original concept – a human body being controlled by something else.

“My own way of thinking about whenever I was animating a Clicker is that these are alive human beings that have something pulling their strings,” Wilson explained. “It’s almost like they would be marionetted by this fungus inside their brain. That’s why you get these motions where, while they move in the right direction, it’s like someone’s pulling them in that direction.”

And as The Last of Us players will know, the introduction to the Clicker is a striking moment.

“The first introduction to a clicker, other than the dead one, is one that’s right up in your face, and we do that on purpose,” Wilson said. “It’s a jump scare that works because, at this point, we’ve kind of only talked them up. You’ve seen the regular runners, and this is the first time that you see [a Clicker] that’s, that’s been out there for a while in the wild.”

But what players will perhaps know is just as frightening as being up close with a Clicker right in Joel’s face is what you hear before you see it, and that’s what gives it its namesake.

Click, click, click

The Clickers earn their name for a reason – without sight, Clickers use these sounds to not only conveniently strike fear in the player, but also to understand their surroundings and track their prey. Though the team knew it wanted to emulate the idea of Clickers using these sounds as a means of echolocation like a bat or dolphin, they still needed to land on what that was.

“One of the most important things was to try to use human sounds as much as possible. We did not want to just make it very creature-y,” PlayStation Studios Senior Director of Sound and Lead Audio on the original The Last of Us Phil Kovats said of the entire Infected soundscape.

“We weren’t sure what we needed. We weren’t sure how we were going to get that. We hired probably four or five actors and spent some time on the stage with them to let them evolve into a sound and figure out what they could do because that’s what they’re good at,” Kovats explained. “We hired very specific actors. And the one actor that found the voice was Misty Lee. And we’d worked with her in the past before, and she’s amazing, and she’s very fun and creative and playful, and she did this back of the throat, kind of dolphin sound, which Derrick Espino and I look at each other, and we’re like, ‘Oh, my God, what is that? This is amazing.’”

Phil and the team took Lee’s sessions and worked with them to establish the depth and range of sounds the Clicker can emit, as the wider Naughty Dog team continued to iterate, refine, and collaborate on what these Infected were capable of. But even with Lee’s work, which was intended for female Clickers, Kovats realized pitching it down or adjusting the audio didn’t sound quite right for what they intended for male Clickers. The answer to that solution came from a surprising place – Kovats himself.

“I found out that I could do the same sound. I think I surprised myself in that. I spent a lot of time laughing with Derrick Espino and Erick Ocampo and recording myself in the sound rooms [at Naughty Dog],” Kovats said, noting how he differentiated his performance a bit. “I’m a little resonate, and using the back of my throat, I always had this tailing whine that would happen as well, too.”

But as players of The Last of Us will already know, and future players will find out, is how dynamic the Clickers are in their vocalization. There is clear and distinct emotion in their soundscape, and that’s very much intentional and achieved thanks to the collaborative work across departments.

“We had to work on creating all these stages and then work with the animation teams and the AI teams to script this as if it was dialog,” Kovats explained. “It’s not just a sound effect. We treated these sounds like dialog of a character.”

Delivering that authenticity meant providing enough depth and believability to the various states players might find a Clicker in, from more docile (though still threatening) moments to how they’d behave in the midst of combat encounters.

“There was a lot of work that went into making sure that you could place the emotion and the state of the character, from unaware, sleeping, there was just breathing and maybe occasional clicks. We saw the animation and how they would have the character twitch, and so we would add little things that would happen like that randomly. We would have buckets of sound that we could call randomly in this to make it seem very organic and natural in that state,” Kovats said.

“And as it started to move…if it was unaware, we would have very quiet vocal tones and nothing that sounded really threatening, but still trying to creep the player out,” he continued. “There were these light clicks as it was navigating its environment…and once it knew something was around, then it was more aggressive sounding, more of the vocal content would be added, as well as higher clicks, louder clicks.”

This variety of sound of course not only adds authenticity and depth to the Clickers to make them feel like more of a threat, but it also serves an important gameplay function – as players choose whether to stealthily avoid these foes, being able to hear their alert level, and their location relative to you, allows the player to better determine how to survive against one of The Last of Us’ most iconic threats.

And that threat continues to linger all these years later, a legacy built from the work across developers and departments throughout Naughty Dog to bring Clickers to life, and continue to do so, most recently via The Last of Us Part I, now available on PlayStation 5 and available for pre-purchase on PC via Steam and the Epic Games Store.

“There were very talented sound designers at the time [of the original game], Derrick Espino and Erick Ocampo, who took on a large mantle of trying to put all that together for the game,” Kovats said. “We worked on it together, and we tried to make sure it was right, and there was a lot of iteration back and forth to get it to be great. And then moving forward into the second game and what people are hearing more now for Part I, Beau Jimenez came in later and reworked a lot of the sounds for the second game. They had a lot more to work with, there were more behaviors, it was more dynamic in the second game and for Part I.”

Bringing the Clickers to life

And of course, the Clickers have now been seen in live action via The Last of Us on HBO. The second episode also marked Druckmann’s television directorial debut and allowed him to bring the franchise’s most iconic Infected to life. In doing so, he had to consider the differences in making such a scary creation so effective in a new medium during a sequence like the museum Clicker encounter.

“One of the biggest differences for an action sequence, we would almost never put that in a cutscene in the game because it’d be like, ‘Oh, I want to play that.’ Those are the parts we want to give control to the player and say, ‘Deal with the situation,’ and that gets you to feel the threat,” Druckmann said. “You can’t do that with the show. So, what the show is a lot about, especially a show like this, was a lot about restraint. When something is horrific like this, it’s scarier when you don’t see it.”

That leads to tense moments where Joel, Ellie, and Tess in the TV show get a glimpse of the Clickers, but don’t immediately come into combat with them.

“We’re going to see glimpses of them, or you’re going to see them in a reflection in the glass. Even at the end of that episode, when that horde [of Infected] is coming towards Tess, we keep them out of focus because it was creepier not to see them, to just feel their presence,” Druckmann said. And it’s scarier, especially in that medium, to see the fear in the character’s eyes. So, a lot of the direction, as far as where you put the camera is, ‘Let’s show the characters’ fear as much as possible, even more so than the thing that’s chasing them.’”

The scarcity of the Clickers, and the tension it elicits in the television version, also plays into some of the differences the creators were challenged by between the different mediums. In the game version, players want to have multiple encounters and test their skills while engaging with stealth and combat mechanics. But too much action in a show could feel repetitive.

“When you have an action sequence, it should be singular. So, one of the things we talked about was the role of action in the show and our belief that we would appreciate the action moments more if they were each unique, separate and apart from each other, each one of them impacting the story directly in a very clear way and either being very small or very big,” executive producer Craig Mazin said.

And there’s one mechanical element in particular that the show’s creatives had to consider when adapting action to TV: they can’t have characters healing as often as players can.

“The other issue with the show where we had to do things differently than the game is games have healing mechanics and healing doesn’t work quite that way on television. It’s just, we can’t crouch, bandage, you know, and be fine. So, violence has a different impact. Smaller bits of violence do a lot more damage, and the damage lasts much, much longer or permanently,” Mazin said.

A shift from game to television also necessitates a change in the choreography of a sequence like this. Viewers don’t need to be taught combat or stealth mechanics like players do, and so the ways in which the characters behave can also be changed to better suit the goals of a scene.

“We don’t just want Joel to sit there and say, ‘Okay, this is what happens.’ In the game, we actually had to do that because we wanted to make it very clear what those mechanics are. Here, we can go, ‘Okay, let’s do it in a very cinematic way with no dialog,’” Druckmann said. “So, Joel’s putting his finger to his mouth and pointing to the ear and trying to explain to Ellie what they need to do, why it’s so important to be quiet and then demonstrate what happens when you’re not. That became really important.”

Action, in general, marked a major difference in philosophy between mediums.

“In the game, you need to have enough action for mastery of mechanics so you can connect with the characters, you get into a flow state,” Druckmann said. “With the show, every action sequence, our approach was, ‘How do we make it character driven?’ Something needs to happen with the characters. They can’t be purely about spectacle. And in this [Clicker] sequence, up until that point, Ellie is really connected to Tess. Only when she’s forced to does she talk to Joel, and it feels like it’s an effort for her to ask him questions. They don’t like each other, but this sequence forces them together and forces Joel to protect her in a way that he didn’t want to, but he can’t help himself.”

In whatever medium, the action of The Last of Us brings to a head the tension, emotions, and themes of the world through every encounter. And the Clickers themselves represent the work of members across Naughty Dog’s development team working together to bring a frightening, but true-to-the-world adversary to life. For those wanting to test their mettle against the Clickers and many other Infected, The Last of Us Part I is currently available on PlayStation 5, and available for pre-purchase on PC via Steam and the Epic Games Store until its release on March 3. The Last of Us airs on HBO and streams on HBO Max.